Americans Love Avocados. It’s Killing Mexico’s Forests.

Illegal deforestation for avocado crops points to a blood-soaked trade with the United States involving threats, abductions and killings.

By Simon Romero and Emiliano Rodríguez Mega

Photographs by César Rodríguez

Reporting from Patuán and other sites around the state of Michoacán where deforestation is advancing.

First the trucks arrived, carrying armed men toward the mist-shrouded mountaintop. Then the flames appeared, sweeping across a forest of towering pines and oaks.

After the fire laid waste to the forest last year, the trucks returned. This time, they carried the avocado plants taking root in the orchards scattered across the once tree-covered summit where townspeople used to forage for mushrooms.

“We never witnessed a blaze on this scale before,” said Maricela Baca Yépez, 46, a municipal official and lifelong resident of Patuán, a town nestled in the volcanic plateaus where Mexico’s Purépecha people have lived for centuries.

Map locates Patuán and several other small towns and villages in the Michoacán state of Mexico.

MEXICO

JALISCO

Zacapu

Ziracuaretiro

Zirahuén

Villa Madero

Patuán

Uruapan

MICHOACÁN

50 MILES

U.S.

MEXICO

Gulf of Mexico

Area of

detail

Mexico City

Pacific

Ocean

GUAT.

500 MILES

In western Mexico forests are being razed at a breakneck pace and while deforestation in places like the Amazon rainforest or Borneo is driven by cattle ranching, gold mining and palm oil farms, in this hot spot, it is fueled by the voracious appetite in the United States for avocados.

A combination of interests, including criminal gangs, landowners, corrupt local officials and community leaders, are involved in clearing forests for avocado orchards, in some cases illegally seizing privately owned land. Virtually all the deforestation for avocados in the last two decades may have violated Mexican law, which prohibits “land-use change” without government authorization.

Since the United States started importing avocados from Mexico less than 40 years ago, consumption has skyrocketed, bolstered by marketing campaigns promoting the fruit as a heart-healthy food and year-round demand for dishes like avocado toast and California rolls. Americans eat three times as many avocados as they did two decades ago.

South of the border, satisfying the demand has come at a high cost, human rights and environmental activists say: the loss of forests, the depletion of aquifers to provide water for thirsty avocado trees and a spike in violence fueled by criminal gangs muscling in on the profitable business.

And while the United States and Mexico both signed a 2021 United Nations agreement to “halt and reverse” deforestation by 2030, the $2.7 billion annual avocado trade between the two countries casts doubts over those climate pledges.

Mexican environmental officials have called on the United States to stop avocados grown on deforested lands from entering the American market, yet U.S. officials have taken no action, according to documents obtained by Climate Rights International, a nonprofit focused on how human rights violations contribute to climate change.

In a new report, the group identified dozens of examples of how orchards on deforested lands supply avocados to American food distributors, which in turn sell them to major American supermarket chains.

Wildfire Tracker The latest updates on fires and danger zones in the West, delivered twice a week.

Fresh Del Monte, one of the largest American avocado distributors, said the industry supported reforestation projects in Mexico. But, in a statement, the company also said that “Fresh Del Monte does not own farms in Mexico,” and relied on “industry collaboration” to ensure growers abided by local laws.

In western Mexico, interviews by The Times with farmers, government officials and Indigenous leaders showed how local people fighting deforestation and water theft have become targets of intimidation, abductions and shootings.

Like deforestation elsewhere, the leveling of Mexico’s pine-oak and oyamel fir forests reduces carbon storage and releases climate-warming gases. But clear-cutting for avocados, which require vast amounts of water, has ignited another crisis by draining aquifers that are a lifeline for many farmers.

One mature avocado tree uses about as much water as 14 mature pine trees, said Jeff Miller, the author of a global history of the avocado.

“You’re putting in deciduous forests of a very water hungry tree and tearing out conifer forests of not so very water hungry trees,” Mr. Miller said. “It’s just wrecking the environment.”

In parts of Mexico already on edge over turf wars among drug cartels, forest loss is fueling new conflicts and raising concerns that Mexican authorities are largely allowing illegal timber harvesters and avocado growers to act with impunity.

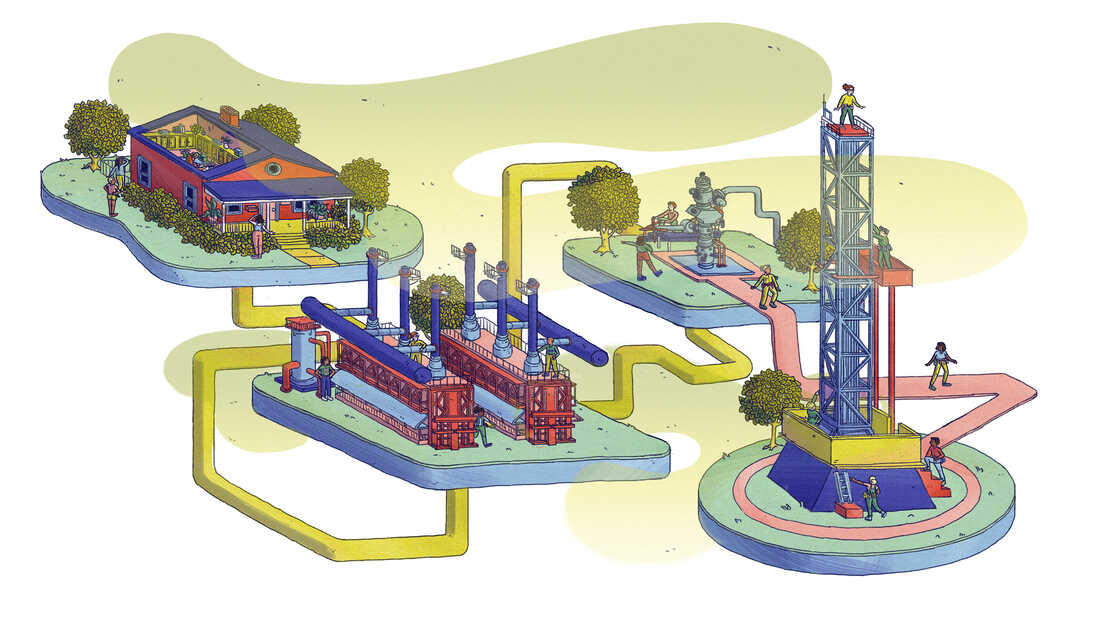

As soon as avocado orchards pop up in deforested areas, illegal wells appear nearby with water transported to orchards through a labyrinthine system of plastic pipes that often pilfer the water supplies of farmers growing traditional crops like tomatoes or corn.

Avocados have been consumed for thousands of years in the region, whose temperate hillsides of porous volcanic soil offer optimal growing conditions. But producing the fruit on an industrial scale for export dates only to the 1990s, when Mexico pressured the United States to end its ban on avocado imports, after opening its own market to American corn.

Mexico now accounts for nearly 90 percent of all avocado shipments to the United States. In Michoacán, the avocado industry employs more than 300,000 workers in the state of 4.8 million, according to government figures.

The powerful association representing the Mexican avocado industry acknowledged deforestation was a problem, but said it was being addressed, including training and equipping forest fire brigades to provide early warnings when fires are started.

“Nobody wants this economic generator that is the Michoacán avocado to end,” said the association’s director, Armando López Orduña.

But in practice, some law enforcement officials say local corruption leads to major forest loss. Last month, an official with the Michoacán state prosecutor’s office for environmental crimes met with two reporters for The Times.

The official, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals, said the environmental unit had been warned by supervisors not to investigate avocado orchards bigger than about 12 acres, even if a complaint was lodged. In turn, the official said, owners needed to pay bribes to supervisors, with amounts based on an orchard’s size.

José Jesús Reyes Mozqueda, the state environmental prosecutor, did not respond directly to the bribery accusations, but said the office had conducted numerous probes into claims of illegal deforestation related to avocados.

In Michoacán, more than 25,000 acres of avocado orchards authorized for export to the United States are on lands that were covered in forest as recently as 2014, according to environmental geographers from the University of Texas at Austin.

(An orchard must be inspected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for a packinghouse to process its avocados for export, though inspections focus on pest control, not on the land’s legal status.)

In 2021, Mexican environmental officials sent a letter to a regional manager for the U.S. Agriculture Department proposing amending an agreement governing the export of Mexican avocados to ensure they did not come from illegally deforested land.

But nothing happened. “It was ignored,” said Daniel Wilkinson, a senior adviser at Climate Rights International.

An Agriculture Department spokesman said “the lack of response to this letter is a ministerial oversight, and not an indication of policy intent.”

U.S. authorities did, however, change the agreement to authorize Jalisco — Mexico’s second-largest avocado producing state — to start exporting the fruit in 2022.

With little outside help, local anti-deforestation activists say they often find themselves waging a lonely and dangerous campaign.

An activist from the village of Villa Madero in Michoacán, who asked not to be identified out of safety concerns, described how in 2021 he was abducted and beaten by kidnappers before being released.

Purépecha leaders from Zirahuén, another Michoacán town, recounted how in 2019 gunmen from a local criminal group broke into their homes and abducted them after the leaders opposed the carving parcels of community-held lands to establish avocado orchards.

“The avocados you’re eating in the United States are bathed in blood,” said one kidnapping victim, a Purépecha man who said he had a weapon pointed at his head and asked not to be identified for fear of his safety.

In another episode that occurred near the Michoacán city of Zacapu, one man who said he had been threatened, Donaciano Arévalo, took the rare step of insisting on being named.

After buying nearly 50 acres of land, Mr. Arévalo said he discovered that men with chain saws were cutting down trees to grow avocados on his parcel, which had been sold without his knowledge.

When he failed to dislodge the squatters, he filed a complaint in 2020 with the local prosecutor’s office describing being threatened by armed men.

“I felt my heart pounding in my chest,” Mr. Arévalo, 60, recounted. “And I said, ‘These guys are going to kill me or they’re going to disappear me or they’re going to hand me over to the criminals.’”

Still, despite the killings of two local property association leaders, Mr. Arévalo pressed ahead with his case to reclaim his land. “I haven’t stopped because it’s the only thing that I was going to leave for my children,” he said.

In Patuán, where the forest burned down last year, townspeople tried mobilizing against deforestation, setting up a 24-hour checkpoint at the town’s entrance to keep out trucks with avocado plants.

But staffing the checkpoint proved time consuming and the effort was abandoned after three months.

The trucks, avocado plants and offers of bribes started rolling in.

“People come to me,” said José León Aguilar, a municipal trustee who grows avocados. “‘You know what, Mr. Commissioner, I offer you 40,000, 50,000 pesos. Let us work.’”

“All this that is happening is our fault, because we are accomplices,” Mr. Aguilar continued. At the same time, he seemed to disavow doing anything illegal. “I never lent myself to bad things,” he said.

Even as the avocado trade is tainted by environmental abuses, violence and corruption, it is likely to continue booming. A study last year estimated that the amount of land in Michoacán used for avocado crops could increase by more than 80 percent by 2050.

“We’re aware that we cannot collapse the state economy,” said Alejandro Méndez, Michoacán’s environmental secretary. “But we are also aware that if we don’t stop this we are going to be left with nothing.”

Simon Romero is a correspondent in Mexico City, covering Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. He has served as The Times’s Brazil bureau chief, Andean bureau chief and international energy correspondent. More about Simon Romero

Emiliano Rodríguez Mega is a reporter and researcher for The Times based in Mexico City, covering Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. More about Emiliano Rodríguez Mega

A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 29, 2023, Section A, Page 4 of the New York edition with the headline: U.S. Appetite for Avocados Is Eating Away at Mexico’s Forests. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe